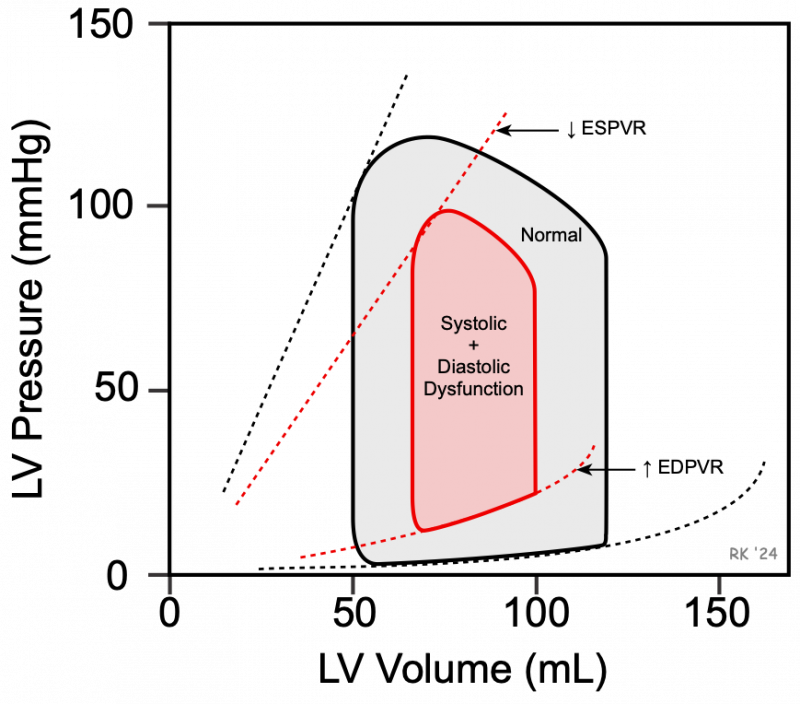

Combined Ventricular Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunction

It is not uncommon for chronic heart failure to have a combination of both systolic and diastolic dysfunction, as illustrated in the figure. The decreased slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) represents a loss of inotropy (systolic dysfunction), and the increased slope of the passive filling curve (end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR) represents diastolic dysfunction caused by reduced ventricular compliance. The resultant pressure-volume loop (red) illustrates how ventricular pressures and volumes are altered by the combination systolic and diastolic dysfunction. In this example, there is a large reduction in stroke volume from 70 to 35 mL (width of pressure-volume loop) because the end-systolic volume is increased and the end-diastolic volume is decreased; the ejection fraction is decreased from 58 to 35%, and stroke work is decreased. The changes shown in the figure assume that heart rate and systemic vascular resistance are both unchanged; however, in patients, both parameters are normally increased because of neurohumoral activation in response to heart failure, which would alter the appearance of the loop. Furthermore, patients will different degrees of systolic and diastolic dysfunction, which would alter the slopes of ESPVR and EDPVR shown in this figure.

It is not uncommon for chronic heart failure to have a combination of both systolic and diastolic dysfunction, as illustrated in the figure. The decreased slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (ESPVR) represents a loss of inotropy (systolic dysfunction), and the increased slope of the passive filling curve (end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship (EDPVR) represents diastolic dysfunction caused by reduced ventricular compliance. The resultant pressure-volume loop (red) illustrates how ventricular pressures and volumes are altered by the combination systolic and diastolic dysfunction. In this example, there is a large reduction in stroke volume from 70 to 35 mL (width of pressure-volume loop) because the end-systolic volume is increased and the end-diastolic volume is decreased; the ejection fraction is decreased from 58 to 35%, and stroke work is decreased. The changes shown in the figure assume that heart rate and systemic vascular resistance are both unchanged; however, in patients, both parameters are normally increased because of neurohumoral activation in response to heart failure, which would alter the appearance of the loop. Furthermore, patients will different degrees of systolic and diastolic dysfunction, which would alter the slopes of ESPVR and EDPVR shown in this figure.

This combination of systolic and diastolic dysfunction, coupled with compensatory volume expansion, can lead to very high left ventricular end-diastolic pressures that can cause pulmonary congestion and edema. This can lead to systemic edema and ascites, particularly when the right ventricle begins to fail.

Revised 01/27/2024

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021)

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021) Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)

Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)