Series and Parallel Vascular Networks

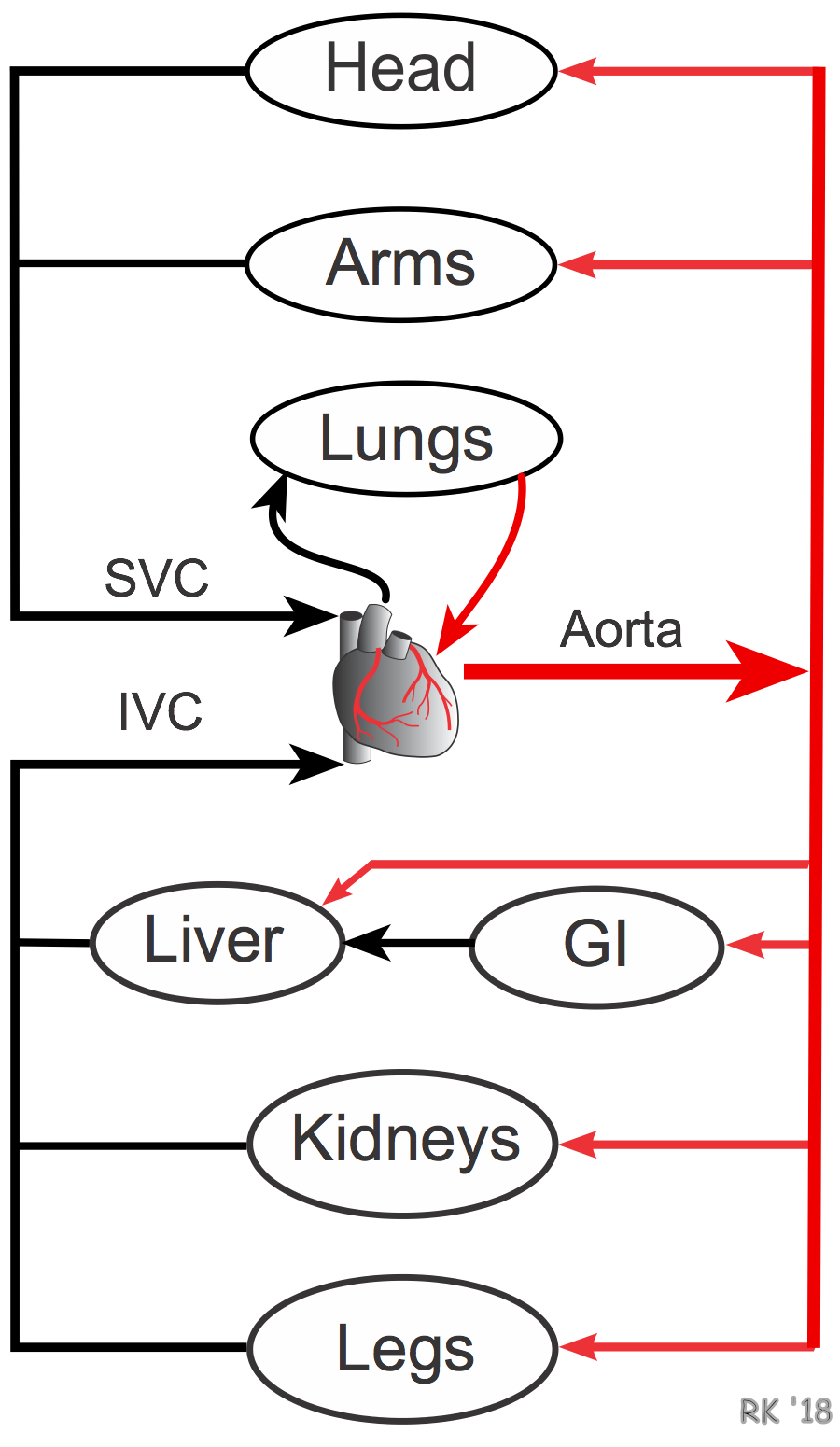

The vascular anatomy of the entire body or for an individual organ comprises both in-series and in-parallel vascular components, as shown to the right. Blood leaves the heart through the aorta from which it is distributed to major organs by large arteries, each of which originates from the aorta. Therefore, these major distributing arteries (e.g., carotid, brachial, superior mesenteric, renal, iliac) are in-parallel with each other. This further means that the vascular networks of most individual organs are in-parallel with other organ networks. For example, the circulations of the head, arms, gastrointestinal system, kidneys, and legs are all parallel circulations. There are some exceptions, notably the gastrointestinal and hepatic circulations, which are partly in-series because the venous drainage from the intestines becomes the hepatic portal vein which supplies most of the blood flow to the liver.

The vascular anatomy of the entire body or for an individual organ comprises both in-series and in-parallel vascular components, as shown to the right. Blood leaves the heart through the aorta from which it is distributed to major organs by large arteries, each of which originates from the aorta. Therefore, these major distributing arteries (e.g., carotid, brachial, superior mesenteric, renal, iliac) are in-parallel with each other. This further means that the vascular networks of most individual organs are in-parallel with other organ networks. For example, the circulations of the head, arms, gastrointestinal system, kidneys, and legs are all parallel circulations. There are some exceptions, notably the gastrointestinal and hepatic circulations, which are partly in-series because the venous drainage from the intestines becomes the hepatic portal vein which supplies most of the blood flow to the liver.

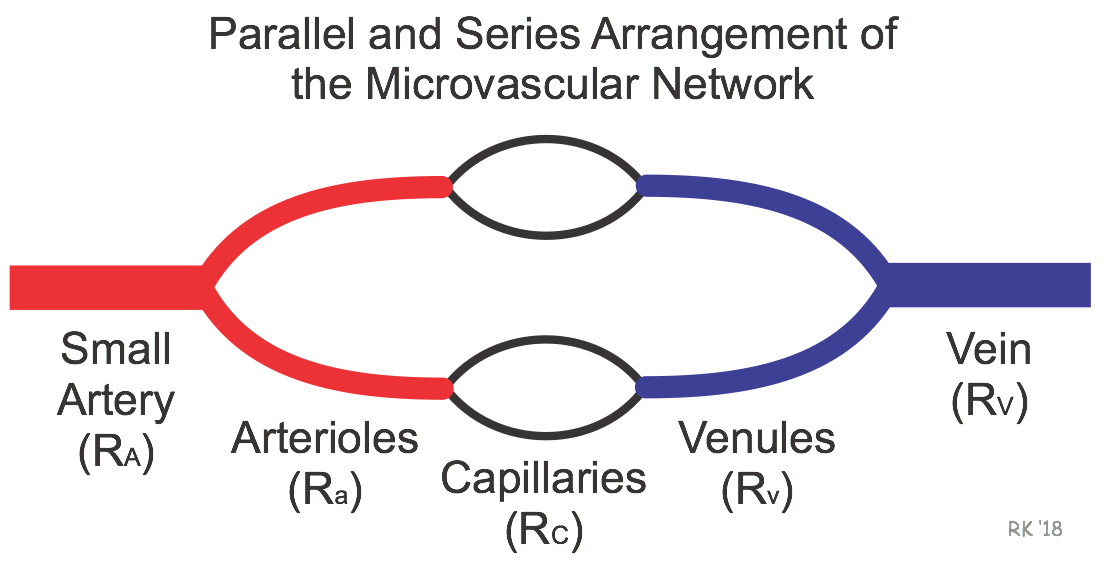

Within an organ, the vessels comprising the microcirculation are arranged in-series and in-parallel (see figure below). A small artery is in-series with its two daughter branches (arterioles), and each of these arteriolar branches is in-parallel to each other. The arterioles give rise to capillaries (in-series connection), which are in-parallel to each other. Therefore, each of the vascular segments depicted in the figure are in-series to each other, although within the segment there are parallel vessels. Furthermore, each vascular segment will have a segmental resistance value (Rx) that is determined by the length and radius of each of the vessels that comprise the segment of parallel vessels (see parallel resistance calculation).

For a series resistance network, the total resistance (RT) equals the sum of the individual resistances. Therefore, for the vessels depicted in the above figure, the total resistance is equal to the sum of the small artery (RA), arterioles (Ra), capillaries (Rc), venules (Rv), and vein (RV) resistances.

RT = RA + Ra + Rc + Rv + RV

The resistance of each segment relative to the total resistance of all the segments determines how changing the resistance of one segment affects total resistance. To illustrate this principle, a relative resistance value can be assigned to each of the five resistance segments in this model. The relative resistances given below are similar to what is observed in a typical vascular bed.

Assume, RA = 20, Ra = 50, Rc = 20, Rv = 6, RV = 4

Therefore, RT = 20 + 50 +20 +6 + 4 = 100

Using this empirical model, we can see that doubling RV from 4 to 8 increases RT from 100 to 104, a 4% increase. In contrast, doubling Ra from 50 to 100 increases RT from 100 to 150, a 50% increase. If this were done for each of the segments, we would find that the arteriolar segment, which has the highest relative resistance, has the greatest effect on total resistance. As a group, changes in diameter (and therefore resistance) of small arteries and arterioles have the greatest influence on vascular resistance because these two vessel segments comprise about 70% of the total resistance in most organs.

The above analysis also explains why the radius of a large, distributing artery must be decreased by over 50% to have a significant effect on organ blood flow. These large arteries comprise only about 1% of the total resistance. Therefore, unlike arterioles, small changes in their diameter have a relatively small effect on total resistance. They must undergo large reductions in diameter before resistance and flow are significantly reduced. This is referred to as a "critical" stenosis. This can be confusing because the Poiseuille's equation shows that resistance to flow is inversely related to diameter to the fourth power. Therefore, a 50% reduction in radius should increase resistance 16-fold (1500% increase); however, total resistance will only increase by about 15% because the large artery resistance is normally only about 1% of the total resistance.

Revised 12/15/2022

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021)

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021) Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)

Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)