Valvular Insufficiency (Regurgitation)

Valvular insufficiency results from valve leaflets not completely sealing when a valve is closed so that regurgitation of blood occurs (backward flow of blood) into the proximal cardiac chamber. Regurgitation results in turbulence and the generation of characteristic heart murmurs.

Aortic and pulmonic valve regurgitation

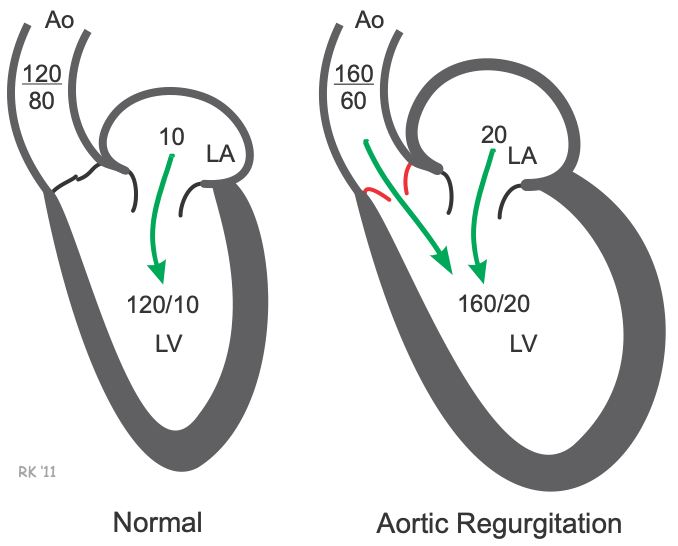

Aortic regurgitation occurs when the aortic valve cannot close completely and blood flows back from the aorta (Ao) into the left ventricle after ejection into the aorta is complete. This back flow occurs while the left ventricle (LV) is also being filled from the left atrium (LA). Because the ventricle is being filled from two sources (aorta and LA), this leads to much greater LV filling; therefore, LV end-diastolic volume increases, which increases LV end-diastolic pressure (20 mmHg in this example). The increased ventricular end-diastolic volume (preload) increases the force of contraction through the Frank-Starling mechanism, which increases the stroke volume into the aorta. This elevates aortic systolic pressure (160 mmHg in this example); however, the aortic diastolic pressure (60 mmHg in this example) is much lower than normal as blood leaves the aorta more rapidly because of backward flow into the LV in addition to the normal forward flow into the systemic circulation. Therefore, a defining characteristic of aortic regurgitation is an increase in aortic pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic pressure). The elevation in LV end-diastolic pressure causes blood to back up into the left atrium and pulmonary veins, which increases left atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and can cause pulmonary congestion and edema. The backward flow of blood into the ventricular chamber during diastole results in a diastolic murmur.

Aortic regurgitation occurs when the aortic valve cannot close completely and blood flows back from the aorta (Ao) into the left ventricle after ejection into the aorta is complete. This back flow occurs while the left ventricle (LV) is also being filled from the left atrium (LA). Because the ventricle is being filled from two sources (aorta and LA), this leads to much greater LV filling; therefore, LV end-diastolic volume increases, which increases LV end-diastolic pressure (20 mmHg in this example). The increased ventricular end-diastolic volume (preload) increases the force of contraction through the Frank-Starling mechanism, which increases the stroke volume into the aorta. This elevates aortic systolic pressure (160 mmHg in this example); however, the aortic diastolic pressure (60 mmHg in this example) is much lower than normal as blood leaves the aorta more rapidly because of backward flow into the LV in addition to the normal forward flow into the systemic circulation. Therefore, a defining characteristic of aortic regurgitation is an increase in aortic pulse pressure (systolic minus diastolic pressure). The elevation in LV end-diastolic pressure causes blood to back up into the left atrium and pulmonary veins, which increases left atrial pressure and pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and can cause pulmonary congestion and edema. The backward flow of blood into the ventricular chamber during diastole results in a diastolic murmur.

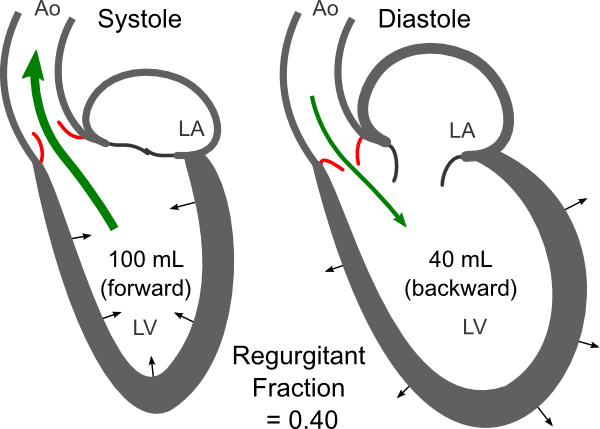

The forward flow across the aortic valve and the regurgitant flow from the aorta back into the ventricle can be visualized and quantified by echocardiography. This enables a calculation of the regurgitant fraction (RF), which indicates the magnitude of the regurgitation. The RF is calculated by dividing the backward regurgitant volume by the total ventricular stroke volume, determined by the different between the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. In the figure, for example, the total forward volume ejected is 100 mL, and the regurgitant volume is 40 mL. In this case, the RF = 0.40 or 40%, and the net forward volume ejected into the aorta for systemic distribution is 60 mL.

The forward flow across the aortic valve and the regurgitant flow from the aorta back into the ventricle can be visualized and quantified by echocardiography. This enables a calculation of the regurgitant fraction (RF), which indicates the magnitude of the regurgitation. The RF is calculated by dividing the backward regurgitant volume by the total ventricular stroke volume, determined by the different between the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. In the figure, for example, the total forward volume ejected is 100 mL, and the regurgitant volume is 40 mL. In this case, the RF = 0.40 or 40%, and the net forward volume ejected into the aorta for systemic distribution is 60 mL.

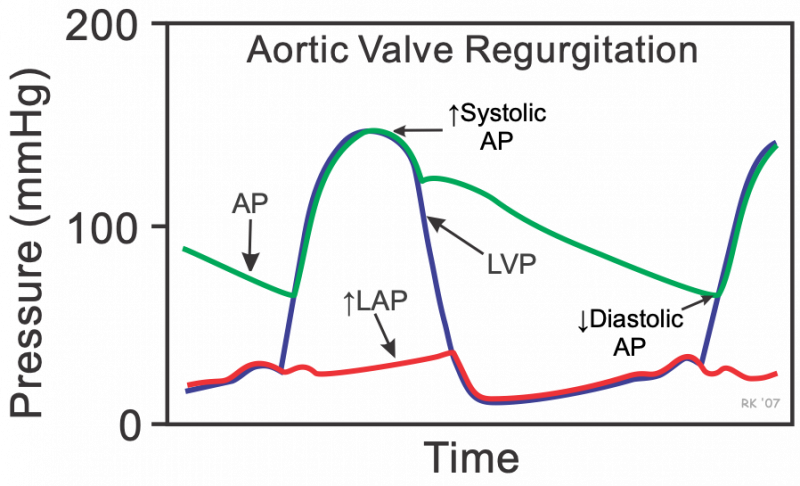

Changes in aortic pressure (AP), left ventricular pressure (LVP) and left atrial pressure (LAP) that can be observed during the cardiac cycle with aortic regurgitation. These pressures differ from those that normally occur (compare with normal cardiac cycle) in that the aortic pulse pressure is greatly increased because of a lower diastolic pressure and elevated systolic pressure. The LAP and LVP pressures are elevated during ventricular filling because of increased atrial and ventricular blood volumes.

Changes in aortic pressure (AP), left ventricular pressure (LVP) and left atrial pressure (LAP) that can be observed during the cardiac cycle with aortic regurgitation. These pressures differ from those that normally occur (compare with normal cardiac cycle) in that the aortic pulse pressure is greatly increased because of a lower diastolic pressure and elevated systolic pressure. The LAP and LVP pressures are elevated during ventricular filling because of increased atrial and ventricular blood volumes.

Early in the course of regurgitant aortic valve disease, there is a large increase in left ventricular end-diastolic pressure and left atrial pressure. The ventricle and atria function on a stiffer portion of their compliance curves, so that the increased volume results in a large rise in end-diastolic pressure. With long-standing regurgitation and volume overload of the chambers, the ventricle and atria dilate anatomically, which attenuates the increase in end-diastolic pressure caused by the increased end-diastolic volume. In other words, remodeling of the chambers results in increased chamber compliance and more normal filling pressures. Ventricular pressure and volume changes during aortic regurgitation can be illustrated using ventricular pressure-volume loops.

A 12-minute recorded lecture on this topic can be viewed by clicking on Aortic Regurgitation Pathophysiology.

Pulmonary valve regurgitation has a similar hemodynamic basis as aortic regurgitation, except that the changes in pressures and volumes occur on the right side of the heart (pulmonary artery, right ventricle, and right atrium).

Mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation

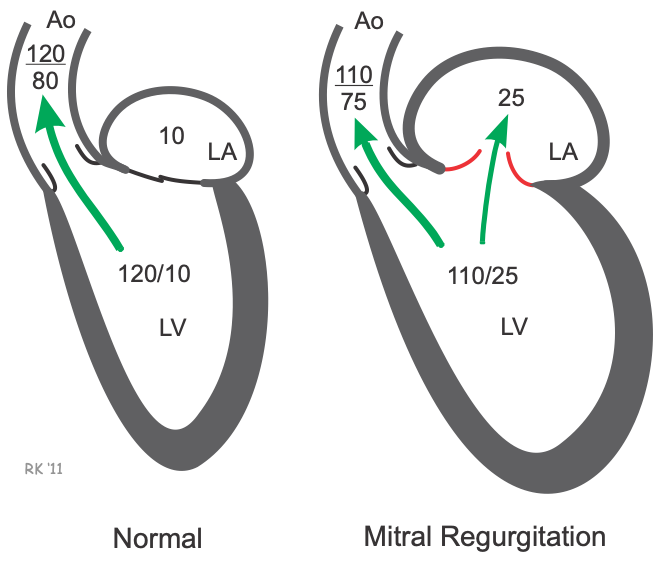

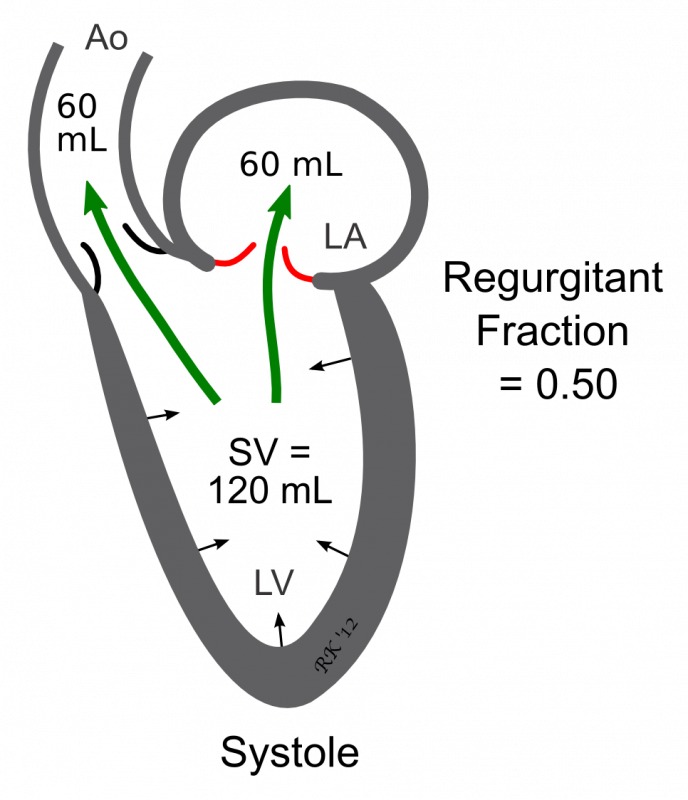

Mitral valve regurgitation occurs when the mitral valve fails to close completely during ventricular systole, which causes blood to flow back (regurgitate) into the left atrium (LA) as the left ventricle (LV) contracts (see figure at right). The left atrium becomes engorged with blood because blood is entering the LA from the LV during ventricular systole as well as from the pulmonary veins. This causes the LA pressure to increase (25 mmHg in this example). During LV filling, the higher pressure of the LA leads to an increase in LV end-diastolic pressure (25 mmHg in this example) and LV end-diastolic volume. This increase in LV preload causes the LV to contract more forcefully (Frank-Starling mechanism), which enables it to increase its stroke volume. Although the LV stroke volume (end-diastolic minus end-systolic volume) is increased, the net amount of blood ejected into the aorta is reduced because part of the LV stroke volume (regurgitant fraction) is also ejected into the LA. If the volume of blood ejected into the aorta is sufficiently reduced, then aortic pressure may fall (110/75 mmHg in this example). In acute mitral regurgitation (e.g., after sudden rupture of the chordae tendineae), the atrial pressure can become very elevated. In chronic mitral regurgitation, the left atrium adapts to the larger volume by dilating (anatomic remodeling), which increases its compliance. Remodeling helps to limit the increases in LA and LV pressures. The backward flow of blood into the LA during ventricular systole results in a holosystolic murmur.

Mitral valve regurgitation occurs when the mitral valve fails to close completely during ventricular systole, which causes blood to flow back (regurgitate) into the left atrium (LA) as the left ventricle (LV) contracts (see figure at right). The left atrium becomes engorged with blood because blood is entering the LA from the LV during ventricular systole as well as from the pulmonary veins. This causes the LA pressure to increase (25 mmHg in this example). During LV filling, the higher pressure of the LA leads to an increase in LV end-diastolic pressure (25 mmHg in this example) and LV end-diastolic volume. This increase in LV preload causes the LV to contract more forcefully (Frank-Starling mechanism), which enables it to increase its stroke volume. Although the LV stroke volume (end-diastolic minus end-systolic volume) is increased, the net amount of blood ejected into the aorta is reduced because part of the LV stroke volume (regurgitant fraction) is also ejected into the LA. If the volume of blood ejected into the aorta is sufficiently reduced, then aortic pressure may fall (110/75 mmHg in this example). In acute mitral regurgitation (e.g., after sudden rupture of the chordae tendineae), the atrial pressure can become very elevated. In chronic mitral regurgitation, the left atrium adapts to the larger volume by dilating (anatomic remodeling), which increases its compliance. Remodeling helps to limit the increases in LA and LV pressures. The backward flow of blood into the LA during ventricular systole results in a holosystolic murmur.

The forward flow across the aortic valve and the regurgitant flow back into the left atrium can be visualized and quantified by echocardiography, and the RF calculated to assess the magnitude of the regurgitation. The RF is calculated by dividing the regurgitant volume into the atrium by the total ventricular stroke volume, determined by the different between the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. In the figure, for example, the total forward volume ejected is 100 mL, and the regurgitant volume is 50 mL. In this case, the RF = 0.50 or 50%, and the net forward volume ejected into the aorta for systemic distribution is 50 mL.

The forward flow across the aortic valve and the regurgitant flow back into the left atrium can be visualized and quantified by echocardiography, and the RF calculated to assess the magnitude of the regurgitation. The RF is calculated by dividing the regurgitant volume into the atrium by the total ventricular stroke volume, determined by the different between the end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes. In the figure, for example, the total forward volume ejected is 100 mL, and the regurgitant volume is 50 mL. In this case, the RF = 0.50 or 50%, and the net forward volume ejected into the aorta for systemic distribution is 50 mL.

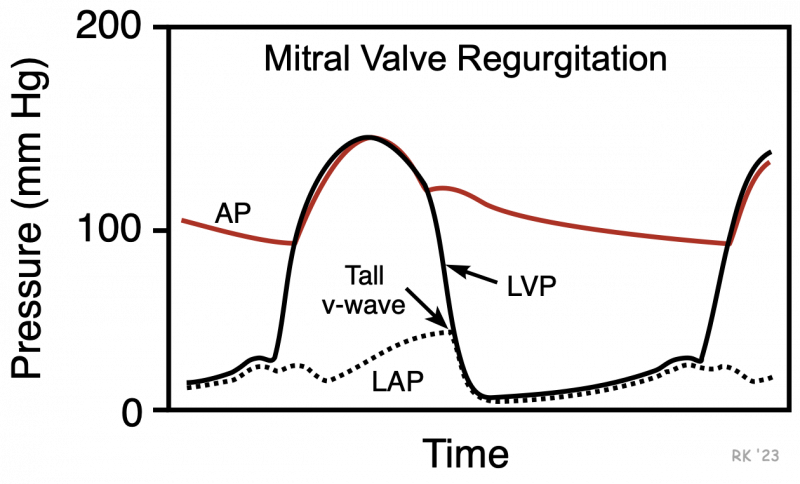

Mitral valve regurgitation affects aortic pressure (AP), left ventricular pressure (LVP) and left atrial pressure (LAP) during the cardiac cycle. Because the left atrium now receives blood from the ventricle and from the pulmonary veins, there is a large increase in atrial pressure throughout the cardiac cycle. This is most apparent at the end of ventricular systole, where a very tall v-wave is observed. LV pressures during diastole are elevated because of elevated LA pressures. Increased left atrial pressures can lead to pulmonary congestion and edema.

Mitral valve regurgitation affects aortic pressure (AP), left ventricular pressure (LVP) and left atrial pressure (LAP) during the cardiac cycle. Because the left atrium now receives blood from the ventricle and from the pulmonary veins, there is a large increase in atrial pressure throughout the cardiac cycle. This is most apparent at the end of ventricular systole, where a very tall v-wave is observed. LV pressures during diastole are elevated because of elevated LA pressures. Increased left atrial pressures can lead to pulmonary congestion and edema.

The changes in left ventricular pressure and volume that occur in response to mitral valve regurgitation can be illustrated by pressure-volume loops.

A 17-minute recorded lecture on this topic can be viewed by clicking on Mitral Regurgitation Pathophysiology.

Tricuspid valve regurgitation has a similar hemodynamic basis as mitral regurgitation, except that the changes in pressures and volumes occur on the right side of the heart (pulmonary artery, right ventricle, and right atrium).

Revised 01/23/2024

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021)

Cardiovascular Physiology Concepts, 3rd edition textbook, Published by Wolters Kluwer (2021) Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)

Normal and Abnormal Blood Pressure, published by Richard E. Klabunde (2013)